Pandas

Table of contents:

- Pandas Datastructures

- Data Indexing (Selection/ Subsets)

- DataFrame Manipulation

- Handling Missing Data

- Data Aggregation (Grouping)

- Statistical Summaries

- Importing Data

- Timeseries with Pandas

Pandas is a specialized Python library for data analysis, especially on humongous datasets. It boasts easy to use functionality for reading and writing data, dealing with missing data, reshaping the dataset, massaging the data by slicing, indexing, inserting and deleting data variables and records. Pandas also have an important groupBy functionality for aggregating data for defined conditions - useful for plotting and computing data summaries for exploration.

Another key strength of Pandas is in re-ordering and cleaning time series data for time-series analysis. In short, Pandas is the go-to tool for data cleaning and data exploration.

Pandas Datastructures

Just like NumPy, Pandas can store and manipulate a multi-dimensional array of data. To handle this, Pandas has the Series and DataFrame data structures.

Series

The Series data structure is for storing a 1-Dimensional array (or vector) of data elements. A series data structure also provides labels to the data items in the form of an index. The user can specify this labels via the index parameter in the Series function, but if the index parameter is left unspecified, a default label of 0 to one minus the size of the data elements are assigned.

To begin with Pandas, we’ll start by importing the Pandas module:

import pandas as pd

Let us consider an example of creating a Series data structure.

# create a Series object

> my_series = pd.Series([2,4,6,8], index=['e1','e2','e3','e4'])

# print out data in Series data structure

> my_series

'Output':

e1 2

e2 4

e3 6

e4 8

dtype: int64

# check the data type of the variable

> type(my_series)

'Output': pandas.core.series.Series

# return the elements of the Series data structure

> my_series.values

'Output': array([2, 4, 6, 8])

# retrieve elements from Series data structure based on their assigned indices

> my_series['e1']

'Output': 2

# return all indices of the Series data structure

> my_series.index

'Output': Index(['e1', 'e2', 'e3', 'e4'], dtype='object')

Elements in a Series data structure can be assigned the same indices

# create a Series object with elements sharing indices

> my_series = pd.Series([2,4,6,8], index=['e1','e2','e1','e2'])

# note the same index assigned to various elements

> my_series

'Output':

e1 2

e2 4

e1 6

e2 8

dtype: int64

# get elements using their index

> my_series['e1']

'Output':

e1 2

e1 6

dtype: int64

DataFrames

A DataFrame is a Pandas data structure for storing and manipulating 2-Dimensional arrays. A 2-Dimensional array is a table-like structure that is similar to an Excel spreadsheet or a relational database table. A DataFrame is a very natural form for storing structured datasets.

A DataFrame consists of rows and columns for storing records of information (in rows) across heterogeneous variables (in columns).

Let’s see examples of working with DataFrames.

# create a data frame

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'age': [15,17,21,29,25], \

'state_of_origin':['Lagos', 'Cross River', 'Kano', 'Abia', 'Benue']})

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15 Lagos

1 17 Cross River

2 21 Kano

3 29 Abia

4 25 Benue

We will observe from the above example that a DataFrame is constructed from a dictionary of records where each value is a Series data structure. Also note that each row has an index that can be assigned when creating the DataFrame, else the default from 0 to one off the number of records in the DataFrame is used. Creating an index manually is usually not feasible except when working with small dummy datasets.

NumPy is frequently used together with Pandas. Let’s import the NumPy library and use some of its functions to demonstrate other ways of creating a quick DataFrame.

import numpy as np

# create a 3x3 dataframe of numbers from the normal distribution

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(3,3),\

columns=['First','Second','Third'])

> my_DF

'Output':

First Second Third

0 -0.211218 -0.499870 -0.609792

1 -0.295363 0.388722 0.316661

2 1.397300 -0.894861 1.127306

# check the dimensions

> my_DF.shape

'Output': (3, 3)

Let’s examine some other operations with DataFrames.

# create a python dictionary

> my_dict = {'State':['Adamawa', 'Akwa-Ibom', 'Yobe', 'Rivers', 'Taraba'], \

'Capital':['Yola','Uyo','Damaturu','Port-Harcourt','Jalingo'], \

'Population':[3178950, 5450758, 2321339, 5198716, 2294800]}

> my_dict

'Output':

{'Capital': ['Yola', 'Uyo', 'Damaturu', 'Port-Harcourt', 'Jalingo'],

'Population': [3178950, 5450758, 2321339, 5198716, 2294800],

'State': ['Adamawa', 'Akwa-Ibom', 'Yobe', 'Rivers', 'Taraba']}

# confirm dictionary type

> type(my_dict)

'Output': dict

# create DataFrame from dictionary

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame(my_dict)

> my_DF

'Output':

Capital Population State

0 Yola 3178950 Adamawa

1 Uyo 5450758 Akwa-Ibom

2 Damaturu 2321339 Yobe

3 Port-Harcourt 5198716 Rivers

4 Jalingo 2294800 Taraba

# check DataFrame type

> type(my_DF)

'Output': pandas.core.frame.DataFrame

# retrieve column names of the DataFrame

> my_DF.columns

'Output': Index(['Capital', 'Population', 'State'], dtype='object')

# the data type of `DF.columns` method is an Index

> type(my_DF.columns)

'Output': pandas.core.indexes.base.Index

# retrieve the DataFrame values as a NumPy ndarray

> my_DF.values

'Output':

array([['Yola', 3178950, 'Adamawa'],

['Uyo', 5450758, 'Akwa-Ibom'],

['Damaturu', 2321339, 'Yobe'],

['Port-Harcourt', 5198716, 'Rivers'],

['Jalingo', 2294800, 'Taraba']], dtype=object)

# the data type of `DF.values` method is an numpy ndarray

type(my_DF.values)

'Output': numpy.ndarray

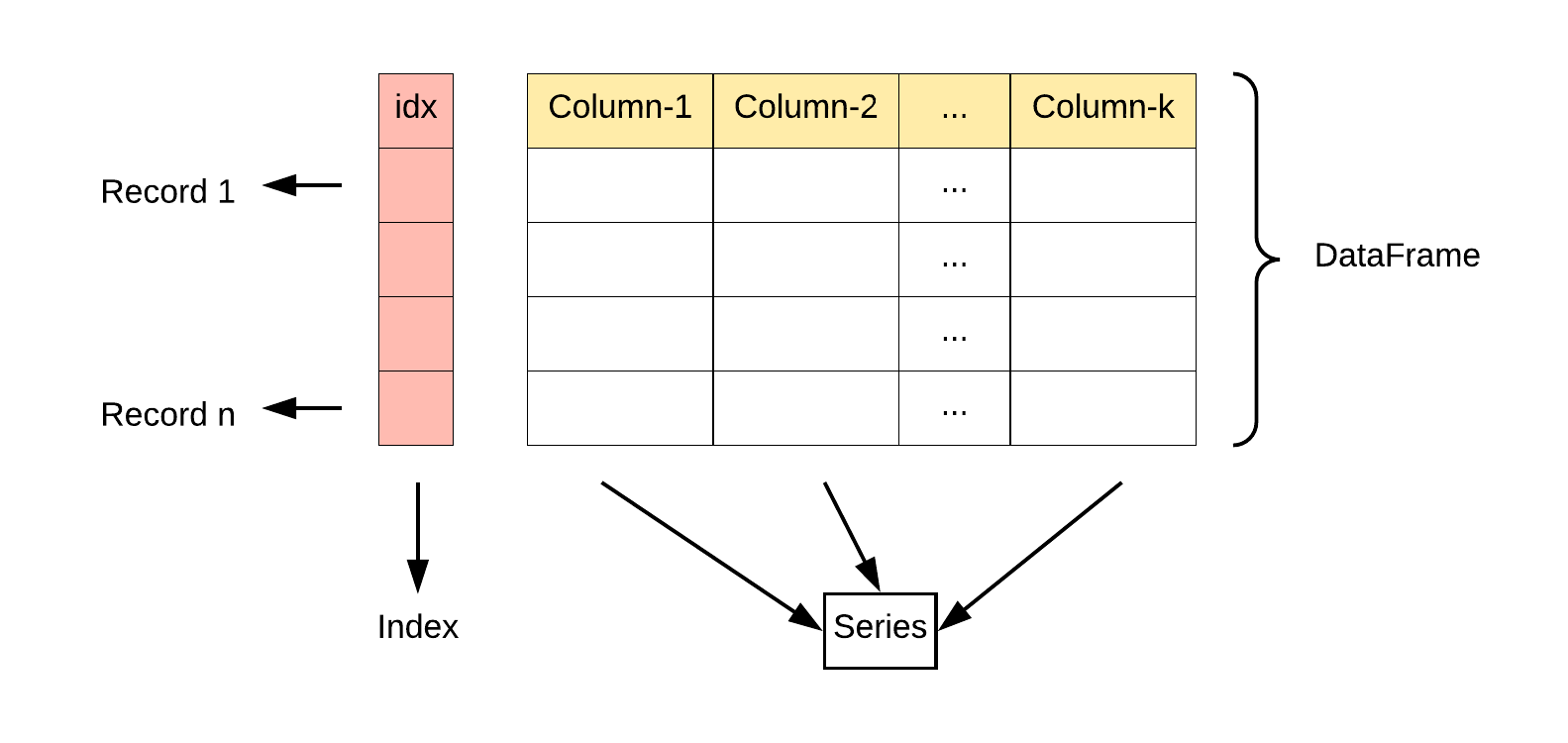

In summary, a DataFrame is a tabular structure for storing a structured dataset where each column contains a Series data structure of records. Here’s an illustration.

Let’s check the data type of each column in the DataFrame

> my_DF.dtypes

'Output':

Capital object

Population int64

State object

dtype: object

An object data type in Pandas represents Strings

Data Indexing (Selection/ Subsets)

Similar to NumPy, Pandas objects can index or subset the dataset to retrieve a specific sub-record of the larger dataset. Note that data indexing returns a new DataFrame or Series if a 2-D or 1-D array is retrieved. They do not, however, alter the original dataset. Let’s go through some examples of indexing a Pandas DataFrame.

First let’s create a dataframe. Observe the default integer indices assigned.

# create the dataframe

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'age': [15,17,21,29,25], \

'state_of_origin':['Lagos', 'Cross River', 'Kano', 'Abia', 'Benue']})

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15 Lagos

1 17 Cross River

2 21 Kano

3 29 Abia

4 25 Benue

Selecting a column from a DataFrame

Remember that the data type of a DataFrame column is a Series because it is a vector or 1-Dimensional array.

> my_DF[['age']]

'Output':

0 15

1 17

2 21

3 29

4 25

Name: age, dtype: int64

# check data type

> type(my_DF['age'])

'Output': pandas.core.series.Series

To select multiple columns, enclose the column names as strings with the double quare-brackets [[ ]]. As an example:

> my_DF[['age','state_of_origin']]

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15 Lagos

1 17 Cross River

2 21 Kano

3 29 Abia

4 25 Benue

Selecting a row from a DataFrame

Pandas makes use of two unique wrapper attributes for indexing rows from a DataFrame or a cell from a Series data structure. These attributes are the iloc and loc - they are also known as indexers. The iloc attribute allows you to select or slice row(s) of a DataFrame using the intrinsic Python index format whereas the loc attribute uses the explicit indices assigned to the DataFrame. If no explicit index is found, loc returns the same value as iloc.

Remember that the data type of a DataFrame row is a Series because it is a vector or 1-Dimensional array.

Let’s select the first row from the DataFrame

# using explicit indexing

> my_DF.loc[0]

'Output':

age 15

state_of_origin Lagos

Name: 0, dtype: object

# using implicit indexing

> my_DF.iloc[0]

'Output':

age 15

state_of_origin Lagos

Name: 0, dtype: object

# let's see the data type

> type(my_DF.loc[0])

'Output': pandas.core.series.Series

Now let’s create a DataFrame with explicit indexing and test out the iloc and loc methods. As you will see Pandas will return an error if we try to use iloc for explicit indexing or try to use loc for implicit Python indexing.

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'age': [15,17,21,29,25], \

'state_of_origin':['Lagos', 'Cross River', 'Kano', 'Abia', 'Benue']},\

index=['a','a','b','b','c'])

# observe the string indices

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

a 15 Lagos

a 17 Cross River

b 21 Kano

b 29 Abia

c 25 Benue

# select using explicit indexing

> my_DF.loc['a']

Out[196]:

age state_of_origin

a 15 Lagos

a 17 Cross River

# lets try to use loc for implicit indexing

> my_DF.loc[0]

'Output':

Traceback (most recent call last):

TypeError: cannot do label indexing on <class 'pandas.core.indexes.base.Index'>

with these indexers [0] of <class 'int'>

Selecting multiple rows and columns from a DataFrame

Let’s use the loc method to select multiple rows and columns from a Pandas DataFrame

# select rows with age greater than 20

> my_DF.loc[my_DF.age > 20]

'Output':

age state_of_origin

2 21 Kano

3 29 Abia

4 25 Benue

# find states of origin with age greater than or equal to 25

> my_DF.loc[my_DF.age >= 25, 'state_of_origin']

'Output':

Out[29]:

3 Abia

4 Benue

Slice cells by row and column from a DataFrame

First let’s create a DataFrame. Remember, we use iloc when no explicit index or row labels are assigned.

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'age': [15,17,21,29,25], \

'state_of_origin':['Lagos', 'Cross River', 'Kano', 'Abia', 'Benue']})

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15 Lagos

1 17 Cross River

2 21 Kano

3 29 Abia

4 25 Benue

# select the third row and second column

> my_DF.iloc[2,1]

'Output': 'Kano'

# slice the first 2 rows - indexed from zero, excluding the final index

> my_DF.iloc[:2,]

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15 Lagos

1 17 Cross River

# slice the last three rows from the last column

> my_DF.iloc[-3:,-1]

'Output':

2 Kano

3 Abia

4 Benue

Name: state_of_origin, dtype: object

DataFrame Manipulation

Removing a Row/ Column

In many cases during the data cleaning process, they may be a need to drop unwanted rows or data variables (i.e., columns). We typically do this using the drop function. The drop function has a parameter axis whose default is 0. If axis is set to 1, it drops columns in a dataset, but if left at the default, rows are dropped from the dataset.

Note that when a column or row is dropped a new DataFrame or Series is returned without altering the original data structure when the attribute inplace is set to True. Let’s see some examples.

# data frame

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'age': [15,17,21,29,25], \

'state_of_origin':['Lagos', 'Cross River', 'Kano', 'Abia', 'Benue']})

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15 Lagos

1 17 Cross River

2 21 Kano

3 29 Abia

4 25 Benue

# drop the 3rd and 4th row

> my_DF.drop([2,4])

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15 Lagos

1 17 Cross River

3 29 Abia

# drop the `age` column and update original DataFrame

> my_DF.drop('age', axis=1, inplace=True)

'Output':

state_of_origin

0 Lagos

1 Cross River

2 Kano

3 Abia

4 Benue

Let’s see examples of removing a row given a condition.

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'age': [15,17,21,29,25], \

'state_of_origin':['Lagos', 'Cross River', 'Kano', 'Abia', 'Benue']})

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15 Lagos

1 17 Cross River

2 21 Kano

3 29 Abia

4 25 Benue

# drop all rows less than 20

> my_DF.drop(my_DF[my_DF['age'] < 20].index, inplace=True)

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

2 21 Kano

3 29 Abia

4 25 Benue

Adding a Row/ Column

We can add a new column to a Pandas DataFrame by using the assign method

# show dataframe

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'age': [15,17,21,29,25], \

'state_of_origin':['Lagos', 'Cross River', 'Kano', 'Abia', 'Benue']})

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15 Lagos

1 17 Cross River

2 21 Kano

3 29 Abia

4 25 Benue

# add column to data frame

> my_DF = my_DF.assign(capital_city = pd.Series(['Ikeja', 'Calabar', \

'Kano', 'Umuahia', 'Makurdi']))

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin capital_city

0 15 Lagos Ikeja

1 17 Cross River Calabar

2 21 Kano Kano

3 29 Abia Umuahia

4 25 Benue Makurdi

We can also add a new DataFrame column by computing some function on another column. Let’s take an example by adding a column computing the absolute difference of the ages from their mean.

> mean_of_age = my_DF['age'].mean()

> my_DF['diff_age'] = my_DF['age'].map(lambda x: abs(x-mean_of_age))

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin diff_age

0 15 Lagos 6.4

1 17 Cross River 4.4

2 21 Kano 0.4

3 29 Abia 7.6

4 25 Benue 3.6

Typically in practice, a fully formed dataset is converted into Pandas for cleaning and data analysis, which does not ideally involve adding a new observation to the dataset. But in the event that this is desired, we can use the append() method to achieve this. However, it may not be a computationally efficient action. Let’s see an example.

# show dataframe

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'age': [15,17,21,29,25], \

'state_of_origin':['Lagos', 'Cross River', 'Kano', 'Abia', 'Benue']})

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15 Lagos

1 17 Cross River

2 21 Kano

3 29 Abia

4 25 Benue

# add a row to data frame

> my_DF = my_DF.append(pd.Series([30 , 'Osun'], index=my_DF.columns), \

ignore_index=True)

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15 Lagos

1 17 Cross River

2 21 Kano

3 29 Abia

4 25 Benue

5 30 Osun

We observe that adding a new row involves passing to the append method, a Series object with the index attribute set to the columns of the main DataFrame. Since typically, in given datasets, the index is nothing more than the assigned defaults, we set the attribute ignore_index to create a new set of default index values with the new row(s).

Data Alignment

Pandas utilizes data alignment to align indices when performing some binary arithmetic operation on DataFrames. If two or more DataFrames in an arithmetic operation do not share a common index, a NaN is introduced denoting missing data. Let’s see examples of this.

# create a 3x3 dataframe - remember randint(low, high, size)

> df_A = pd.DataFrame(np.random.randint(1,10,[3,3]),\

columns=['First','Second','Third'])

> df_A

'Output':

First Second Third

0 2 3 9

1 8 7 7

2 8 6 4

# create a 4x3 dataframe

> df_B = pd.DataFrame(np.random.randint(1,10,[4,3]),\

columns=['First','Second','Third'])

> df_B

'Output':

First Second Third

0 3 6 3

1 2 2 1

2 9 3 8

3 2 9 2

# add df_A and df_B together

> df_A + df_B

'Output':

First Second Third

0 5.0 9.0 12.0

1 10.0 9.0 8.0

2 17.0 9.0 12.0

3 NaN NaN NaN

> divide both dataframes

> df_A / df_B

'Output':

First Second Third

0 0.666667 0.5 3.0

1 4.000000 3.5 7.0

2 0.888889 2.0 0.5

3 NaN NaN NaN

If we do not want a NaN signifying missing values to be imputed, we can use the fill_value attribute to substitute with a default value. However, to take advantage of the fill_value attribute, we have to use the Pandas arithmetic methods: add(), sub(), mul(), div(), floordiv(), mod(), and pow() for addition, subtraction, multiplication, integer division, numeric division, reminder division and exponentiation. Let’s see examples.

> df_A.add(df_B, fill_value=10)

'Output':

First Second Third

0 5.0 9.0 12.0

1 10.0 9.0 8.0

2 17.0 9.0 12.0

3 12.0 19.0 12.0

Combining Datasets

We may need to combine two or more data sets together, Pandas provides methods for such operations. We would consider the simple case of combining data frames with shared column names using the concat method.

# combine two dataframes column-wise

> pd.concat([df_A, df_B])

'Output':

First Second Third

0 2 3 9

1 8 7 7

2 8 6 4

0 3 6 3

1 2 2 1

2 9 3 8

3 2 9 2

Observe that the concat method preserves indices by default. We can also concatenate or combine two dataframes by rows (or horizontally). This is done by setting the axis parameter to 1.

# combine two dataframes horizontally

> pd.concat([df_A, df_B], axis=1)

'Output':

Out[246]:

First Second Third First Second Third

0 2.0 3.0 9.0 3 6 3

1 8.0 7.0 7.0 2 2 1

2 8.0 6.0 4.0 9 3 8

3 NaN NaN NaN 2 9 2

Handling Missing Data

Dealing with missing data is an integral part of the Data cleaning/ data analysis process. Moreover, some machine learning algorithms will not work in the presence of missing data. Let’s see some simple Pandas methods for identifying and removing missing data, as well as imputing values into missing data.

Identifying missing data

# lets create a data frame with missing data

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'age': [15,17,np.nan,29,25], \

'state_of_origin':['Lagos', 'Cross River', 'Kano', 'Abia', np.nan]})

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15.0 Lagos

1 17.0 Cross River

2 NaN Kano

3 29.0 Abia

4 25.0 NaN

Let’s check for missing data in this data frame. The isnull() method will return True where there is a missing data, whereas the notnull() function returns False.

> my_DF.isnull()

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 False False

1 False False

2 True False

3 False False

4 False True

However, if we want a single answer (i.e., either True or False) to report if there is a missing data in the data frame, we will first convert the DataFrame to a NumPy array and use the function any().

The any function returns True when at least one of the elements in the dataset is True. In this case, isnull() returns a DataFrame of booleans where True designates a cell with a missing value.

Let’s see how that works

> my_DF.isnull().values.any()

'Output': True

Removing missing data

Pandas has a function dropna() which is used to filter or remove missing data from a DataFrame. dropna() returns a new DataFrame without missing data. Let’s see examples of how this works

# let's see our dataframe with missing data

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'age': [15,17,np.nan,29,25], \

'state_of_origin':['Lagos', 'Cross River', 'Kano', 'Abia', np.nan]})

> my_DF

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15.0 Lagos

1 17.0 Cross River

2 NaN Kano

3 29.0 Abia

4 25.0 NaN

# let's run dropna() to remove all rows with missing values

> my_DF.dropna()

'Output':

age state_of_origin

0 15.0 Lagos

1 17.0 Cross River

3 29.0 Abia

As we will observe from the above code-block, dropna() drops all rows that contain a missing value. But we may not want that. We may rather, for example, want to drop columns with missing data, or drop rows where all the observations are missing or better still remove consequent on the number of observations present in a particular row.

Let’s see examples of this options. First let’s expand our example dataset

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'Capital': ['Yola', np.nan, np.nan, 'Port-Harcourt', 'Jalingo'],

'Population': [3178950, np.nan, 2321339, np.nan, 2294800],

'State': ['Adamawa', np.nan, 'Yobe', np.nan, 'Taraba'],

'LGAs': [22, np.nan, 17, 23, 16]})

> my_DF

'Output':

Capital LGAs Population State

0 Yola 22.0 3178950.0 Adamawa

1 NaN NaN NaN NaN

2 NaN 17.0 2321339.0 Yobe

3 Port-Harcourt 23.0 NaN NaN

4 Jalingo 16.0 2294800.0 Taraba

Drop columns with NaN. This option is not often used in practice.

> my_DF.dropna(axis=1)

'Output':

Empty DataFrame

Columns: []

Index: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

Drop rows where all the observations are missing.

> my_DF.dropna(how='all')

'Output':

Capital LGAs Population State

0 Yola 22.0 3178950.0 Adamawa

2 NaN 17.0 2321339.0 Yobe

3 Port-Harcourt 23.0 NaN NaN

4 Jalingo 16.0 2294800.0 Taraba

Drop rows based on an observation threshold. By adjusting the thresh attribute, we can drop rows where the number of observations in the row is less than the thresh value.

# drop rows where number of NaN are less than 3

> my_DF.dropna(thresh=3)

'Output':

Capital LGAs Population State

0 Yola 22.0 3178950.0 Adamawa

2 NaN 17.0 2321339.0 Yobe

4 Jalingo 16.0 2294800.0 Taraba

Imputing values into missing data

Imputing values as substitutes for missing data is a standard practice in preparing data for Machine Learning. Pandas has a fillna() function for this purpose. A simple approach is to fill NaNs with zeros.

> my_DF.fillna(0) # we can also run my_DF.replace(np.nan, 0)

'Output':

Capital LGAs Population State

0 Yola 22.0 3178950.0 Adamawa

1 0 0.0 0.0 0

2 0 17.0 2321339.0 Yobe

3 Port-Harcourt 23.0 0.0 0

4 Jalingo 16.0 2294800.0 Taraba

Another tactic is to fill missing values with the mean of the column value.

> my_DF.fillna(my_DF.mean())

'Output':

Capital LGAs Population State

0 Yola 22.0 3178950.0 Adamawa

1 NaN 19.5 2598363.0 NaN

2 NaN 17.0 2321339.0 Yobe

3 Port-Harcourt 23.0 2598363.0 NaN

4 Jalingo 16.0 2294800.0 Taraba

Data Aggregation (Grouping)

We will touch briefly on a common practice in Data Science, and that is grouping a set of data attributes, either for retrieving some group statistics or applying a particular set of functions to the group. Grouping is commonly used for data exploration and plotting graphs to understand more about the data set. Missing data are automatically excluded in a grouping operation.

Let’s see examples of how this works

# create a data frame

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame({'Sex': ['M', 'F', 'M', 'F','M', 'F','M', 'F'],

'Age': np.random.randint(15,60,8),

'Salary': np.random.rand(8)*10000})

> my_DF

'Output':

Age Salary Sex

0 54 6092.596170 M

1 57 3148.886141 F

2 37 5960.916038 M

3 23 6713.133849 F

4 34 5208.240349 M

5 25 2469.118934 F

6 50 1277.511182 M

7 54 3529.201109 F

Let’s find the mean age and salary for observations in our dataset grouped by Sex.

> my_DF.groupby('Sex').mean()

'Output':

Age Salary

Sex

F 39.75 3965.085008

M 43.75 4634.815935

We can group by more than one variable. In this case for each Sex group, also group the age and find the mean of the other numeric variables.

> my_DF.groupby([my_DF['Sex'], my_DF['Age']]).mean()

'Output':

Salary

Sex Age

F 23 6713.133849

25 2469.118934

54 3529.201109

57 3148.886141

M 34 5208.240349

37 5960.916038

50 1277.511182

54 6092.596170

Also, we can use a variable as a group key to run a group function on another variable or sets of variables.

> my_DF['Age'].groupby(my_DF['Salary']).mean()

'Output':

Salary

1277.511182 50

2469.118934 25

3148.886141 57

3529.201109 54

5208.240349 34

5960.916038 37

6092.596170 54

6713.133849 23

Name: Age, dtype: int64

Statistical Summaries

Descriptive statistics is an essential component of the Data Science pipeline. By investigating the properties of the dataset, we can gain a better understanding of the data and the relationship between the variables. This information is useful in making decisions about the type of data transformations to carry out or the types of learning algorithms to spot-check. Let’s see some examples of simple statistical functions in Pandas.

First, we’ll create a Pandas dataframe

> my_DF = pd.DataFrame(np.random.randint(10,80,[7,4]),\

columns=['First','Second','Third', 'Fourth'])

'Output':

First Second Third Fourth

0 47 32 66 52

1 37 66 16 22

2 24 16 63 36

3 70 47 62 12

4 74 61 44 18

5 65 73 21 37

6 44 47 23 13

Use the describe function to obtain summary statistics of a dataset. Eight statistical measures are displayed. They are: count, mean, standard deviation, minimum value, 25th percentile, 50th percentile or median, 75th percentile and the maximum value.

> my_DF.describe()

'Output':

First Second Third Fourth

count 7.000000 7.000000 7.000000 7.000000

mean 51.571429 48.857143 42.142857 27.142857

std 18.590832 19.978560 21.980511 14.904458

min 24.000000 16.000000 16.000000 12.000000

25% 40.500000 39.500000 22.000000 15.500000

50% 47.000000 47.000000 44.000000 22.000000

75% 67.500000 63.500000 62.500000 36.500000

max 74.000000 73.000000 66.000000 52.000000

Correlation

Correlation shows how much relationship exists between two variables. Parametric machine learning methods such as logistic and linear regression can take a performance hit when variables are highly correlated. The correlation values range from -1 to 1, with 0 indicating no correlation at all. -1 signifies that the variables are strongly negatively correlated while 1 shows that the variables are strongly positively correlated. In practice, it is safe to eliminate variables that have a correlation value greater than -0.7 or 0.7. A common correlation estimate in use is the Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient.

> my_DF.corr(method='pearson')

'Output':

First Second Third Fourth

First 1.000000 0.587645 -0.014100 -0.317333

Second 0.587645 1.000000 -0.768495 -0.345265

Third -0.014100 -0.768495 1.000000 0.334169

Fourth -0.317333 -0.345265 0.334169 1.000000

Skewness

Another important statistical metric is the skewness of the dataset. Skewness is when a bell-shaped or Normal distribution is shifted towards the right or the left. Pandas offer a convenient function called skew() to check the skewness of each variable. Values close to 0 are more normally distributed with less skew.

> my_DF.skew()

'Output':

First -0.167782

Second -0.566914

Third -0.084490

Fourth 0.691332

dtype: float64

Importing Data

Again, getting data into the programming environment for analysis is a fundamental and first step for any data analytics or machine learning task. In practice, data usually comes in a comma separated value, csv format.

> my_DF = pd.read_csv('link_to_file/csv_file', sep=',', header = None)

To export a DataFrame back to csv

> my_DF.to_csv('file_name.csv')

Timeseries with Pandas

One of the core strength of Pandas is its powerful set of functions for manipulating Timeseries datasets. A couple of these functions are covered in this material.

Importing a Dataset with a DateTime column

When importing a dataset that has a column containing datetime entries. Pandas has an attribite in the read_csv method called parse_dates that converts the datetime column from strings into Pandas date datatype. The attribute index_col uses the the column of datetimes as an index to the DataFrame.

The method head() prints out the first 5 rows of the DataFrame, while the method tail() prints out the last 5 rows of the DataFrame. This function is very useful for taking a peek at a large DataFrame without having to bear the computational cost of printing it out entirely.

# load the data

> data = pd.read_csv('crypto-markets.csv', parse_dates=['date'], index_col='date')

> data.head()

'Output':

slug symbol name ranknow open high low close volume market close_ratio spread

date

2013-04-28 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 135.30 135.98 132.10 134.21 0 1500520000 0.5438 3.88

2013-04-29 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 134.44 147.49 134.00 144.54 0 1491160000 0.7813 13.49

2013-04-30 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 144.00 146.93 134.05 139.00 0 1597780000 0.3843 12.88

2013-05-01 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 139.00 139.89 107.72 116.99 0 1542820000 0.2882 32.17

2013-05-02 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 116.38 125.60 92.28 105.21 0 1292190000 0.3881 33.32

Let’s examine the index of the imported data, notice that they are the datetime entries.

# get the row indices

> data.index

'Output':

DatetimeIndex(['2013-04-28', '2013-04-29', '2013-04-30', '2013-05-01',

'2013-05-02', '2013-05-03', '2013-05-04', '2013-05-05',

'2013-05-06', '2013-05-07',

...

'2018-01-01', '2018-01-02', '2018-01-03', '2018-01-04',

'2018-01-05', '2018-01-06', '2018-01-07', '2018-01-08',

'2018-01-09', '2018-01-10'],

dtype='datetime64[ns]', name='date', length=659373, freq=None)

Selection Using DatetimeIndex

The DatetimeIndex can be used to select the observations of the dataset in various interesting ways. For example, we can select the observation of an exact day, or the observations belonging to a particular month or year. More the selected observation can be subsetted by columns and grouped to give more insight in understanding the dataset.

Let’s see some examples

Select a particular date

# select a particular date

> data['2018-01-05'].head()

'Output':

slug symbol name ranknow open high \

date

2018-01-05 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 15477.20 17705.20

2018-01-05 ethereum ETH Ethereum 2 975.75 1075.39

2018-01-05 ripple XRP Ripple 3 3.30 3.56

2018-01-05 bitcoin-cash BCH Bitcoin Cash 4 2400.74 2648.32

2018-01-05 cardano ADA Cardano 5 1.17 1.25

low close volume market \

date

2018-01-05 15202.800000 17429.500000 23840900000 259748000000

2018-01-05 956.330000 997.720000 6683150000 94423900000

2018-01-05 2.830000 3.050000 6288500000 127870000000

2018-01-05 2370.590000 2584.480000 2115710000 40557600000

2018-01-05 0.903503 0.999559 508100000 30364400000

close_ratio spread

date

2018-01-05 0.8898 2502.40

2018-01-05 0.3476 119.06

2018-01-05 0.3014 0.73

2018-01-05 0.7701 277.73

2018-01-05 0.2772 0.35

# select a range of dates

> data['2018-01-05':'2018-01-06'].head()

'Output':

slug symbol name ranknow open high low \

date

2018-01-05 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 15477.20 17705.20 15202.80

2018-01-06 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 17462.10 17712.40 16764.60

2018-01-05 ethereum ETH Ethereum 2 975.75 1075.39 956.33

2018-01-06 ethereum ETH Ethereum 2 995.15 1060.71 994.62

2018-01-05 ripple XRP Ripple 3 3.30 3.56 2.83

close volume market close_ratio spread

date

2018-01-05 17429.50 23840900000 259748000000 0.8898 2502.40

2018-01-06 17527.00 18314600000 293091000000 0.8044 947.80

2018-01-05 997.72 6683150000 94423900000 0.3476 119.06

2018-01-06 1041.68 4662220000 96326500000 0.7121 66.09

2018-01-05 3.05 6288500000 127870000000 0.3014 0.73

Select a month

# select a particular month

> data['2018-01'].head()

'Output':

slug symbol name ranknow open high low \

date

2018-01-01 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 14112.2 14112.2 13154.7

2018-01-02 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 13625.0 15444.6 13163.6

2018-01-03 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 14978.2 15572.8 14844.5

2018-01-04 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 15270.7 15739.7 14522.2

2018-01-05 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 15477.2 17705.2 15202.8

close volume market close_ratio spread

date

2018-01-01 13657.2 10291200000 236725000000 0.5248 957.5

2018-01-02 14982.1 16846600000 228579000000 0.7972 2281.0

2018-01-03 15201.0 16871900000 251312000000 0.4895 728.3

2018-01-04 15599.2 21783200000 256250000000 0.8846 1217.5

2018-01-05 17429.5 23840900000 259748000000 0.8898 2502.4

Select a year

# select a particular year

> data['2018'].head()

'Output':

slug symbol name ranknow open high low \

date

2018-01-01 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 14112.2 14112.2 13154.7

2018-01-02 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 13625.0 15444.6 13163.6

2018-01-03 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 14978.2 15572.8 14844.5

2018-01-04 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 15270.7 15739.7 14522.2

2018-01-05 bitcoin BTC Bitcoin 1 15477.2 17705.2 15202.8

close volume market close_ratio spread

date

2018-01-01 13657.2 10291200000 236725000000 0.5248 957.5

2018-01-02 14982.1 16846600000 228579000000 0.7972 2281.0

2018-01-03 15201.0 16871900000 251312000000 0.4895 728.3

2018-01-04 15599.2 21783200000 256250000000 0.8846 1217.5

2018-01-05 17429.5 23840900000 259748000000 0.8898 2502.4

Subset Data Columns and Find Summaries

Get the closing prices of Bitcoin stocks for the Month of January

> data.loc[data.slug == 'bitcoin', 'close']['2018-01']

'Output':

date

2018-01-01 13657.2

2018-01-02 14982.1

2018-01-03 15201.0

2018-01-04 15599.2

2018-01-05 17429.5

2018-01-06 17527.0

2018-01-07 16477.6

2018-01-08 15170.1

2018-01-09 14595.4

2018-01-10 14973.3

Find the mean market value of Ethereum for the Month of January

> data.loc[data.slug == 'ethereum', 'market']['2018-01'].mean()

'Output':

96739480000.0

Resampling datetime objects

A Pandas DataFrame with an index of DatetimeIndex, PeriodIndex, or TimedeltaIndex can be resampled to any of the date time frequencies from seconds, to minutes, to months. Let’s see some examples.

Let’s get the average monthly closing values for Litecoin.

> data.loc[data.slug == 'bitcoin', 'close'].resample('M').mean().head()

'Output':

date

2013-04-30 139.250000

2013-05-31 119.993226

2013-06-30 107.761333

2013-07-31 90.512258

2013-08-31 113.905161

Freq: M, Name: close, dtype: float64

Get the average weekly market value of Bitcoin Cash.

> data.loc[data.symbol == 'BCH', 'market'].resample('W').mean().head()

'Output':

date

2017-07-23 0.000000e+00

2017-07-30 0.000000e+00

2017-08-06 3.852961e+09

2017-08-13 4.982661e+09

2017-08-20 7.355117e+09

Freq: W-SUN, Name: market, dtype: float64

Convert to datetime datatype using to_datetime

Pandas uses the to_datetime method to convert strings to Pandas datetime datatype. The to_datetime method is smart enough to infer a datetime representation from a string of dates passed with different formats. The default output format of to_datetime is in the following order year, month, day, minute, second, millisecond, microsecond, nanosecond.

The input to to_datetime is recognized as month, day, year. Although can easily be modified by setting the attributes dayfirst or yearfirst to True.

For example, if dayfirst is set to True, the input is recognized as day, month, year.

Let’s see an example of this.

# create list of dates

> my_dates = ['Friday, May 11, 2018', '11/5/2018', '11-5-2018', '5/11/2018', '2018.5.11']

> pd.to_datetime(my_dates)

'Output':

DatetimeIndex(['2018-05-11', '2018-11-05', '2018-11-05', '2018-05-11',

'2018-05-11'],

dtype='datetime64[ns]', freq=None)

Let’s set dayfirst to True. Observe that the first input in the string is treated as a day in the output.

# set dayfirst to True

> pd.to_datetime('5-11-2018', dayfirst = True)

'Output':

Timestamp('2018-11-05 00:00:00')

The shift() method

A typical step in a timeseries use-case is to convert the timeseries dataset into a supervised learning framework for predicting the outcome for a given time instant. The shift() method is used to adjust a Pandas DataFrame column by shifting the observations forwards or backward. If the observations are pulled backward (or lagged), NaNs are attached at the tail of the column. But if the values are pushed forward, the head of the column will contain NaNs. This step is important for adjusting the target variable of a dataset to predict outcomes $n$-days or steps or instances into the future. Let’s see some examples

Subset columns for the observations related to Bitcoin Cash.

# subset a few columns

> data_subset_BCH = data.loc[data.symbol == 'BCH', ['open','high','low','close']]

> data_subset_BCH.head()

'Output':

open high low close

date

2017-07-23 555.89 578.97 411.78 413.06

2017-07-24 412.58 578.89 409.21 440.70

2017-07-25 441.35 541.66 338.09 406.90

2017-07-26 407.08 486.16 321.79 365.82

2017-07-27 417.10 460.97 367.78 385.48

Now let’s create a target variable that contains the closing rates 3 days into the future.

> data_subset_BCH['close_4_ahead'] = data_subset_BCH['close'].shift(-4)

> data_subset_BCH.head()

'Output':

open high low close close_4_ahead

date

2017-07-23 555.89 578.97 411.78 413.06 385.48

2017-07-24 412.58 578.89 409.21 440.70 406.05

2017-07-25 441.35 541.66 338.09 406.90 384.77

2017-07-26 407.08 486.16 321.79 365.82 345.66

2017-07-27 417.10 460.97 367.78 385.48 294.46

Observe that the tail of the column close_4_head contains NaNs.

> data_subset_BCH.tail()

'Output':

open high low close close_4_ahead

date

2018-01-06 2583.71 2829.69 2481.36 2786.65 2895.38

2018-01-07 2784.68 3071.16 2730.31 2786.88 NaN

2018-01-08 2786.60 2810.32 2275.07 2421.47 NaN

2018-01-09 2412.36 2502.87 2346.68 2391.56 NaN

2018-01-10 2390.02 2961.20 2332.48 2895.38 NaN

Rolling Windows

Pandas provides a function called rolling() to find the rolling or moving statistics of values in a column over a specified window. The window is the “number of observations used in calculating the statistic”. So we can find the rolling sums or rolling means of a variable. These statistics are vital when working with timeseries datasets. Let’s see some examples

Let’s find the rolling means for the closing variable over a 30-day window.

# find the rolling means for Bitcoin cash

> rolling_means = data_subset_BCH['close'].rolling(window=30).mean()

The first few values of the rolling_means variable contain NaNs because the method computes the rolling statistic from the earliest time to the latest time in the dataset. Let’s print out the first 5 values using the head method.

> rolling_means.head()

Out[75]:

date

2017-07-23 NaN

2017-07-24 NaN

2017-07-25 NaN

2017-07-26 NaN

2017-07-27 NaN

Now see the last 5 values using the tail method.

> rolling_means.tail()

'Output':

date

2018-01-06 2403.932000

2018-01-07 2448.023667

2018-01-08 2481.737333

2018-01-09 2517.353667

2018-01-10 2566.420333

Name: close, dtype: float64

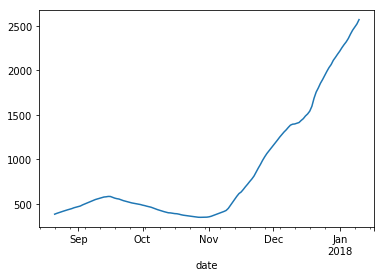

Let’s do a quick plot of the rolling means using the Pandas plotting function. More on plotting in the next section.

# plot the rolling means for Bitcoin cash

> data_subset_BCH['close'].rolling(window=30).mean().plot(label='Rolling Average over 30 days')